This piece was first published by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung in a shortened version. It is also published in various national newspapers, including Le Monde.

The eurozone remains in a deep, largely macro-economic crisis. A robust global economy and falling oil prices have supported Europe’s economy for some time, but by now it is clear that the eurozone will only be able to pull itself out of this crisis by means of more decisive action. One response, the recent easing of monetary policy by the European Central Bank (ECB), has, for the most part, been sharply and one-sidedly criticised in Germany. Monetary policy inaction seems to be the preferred option of many in Germany.

Yet many critics of the ECB have left a number of important questions unanswered. What would happen if the ECB failed to respond to the excessively low inflation and the weak economy? And what economic policy would be suitable under the current circumstances, if not monetary policy? It is not sufficient to merely criticise and say “no”. Germany has an important role to play in formulating constructive answers to the European crisis, including an open, constructive, macro-economic debate that is based on empirical evidence and considers the monetary union as a whole.

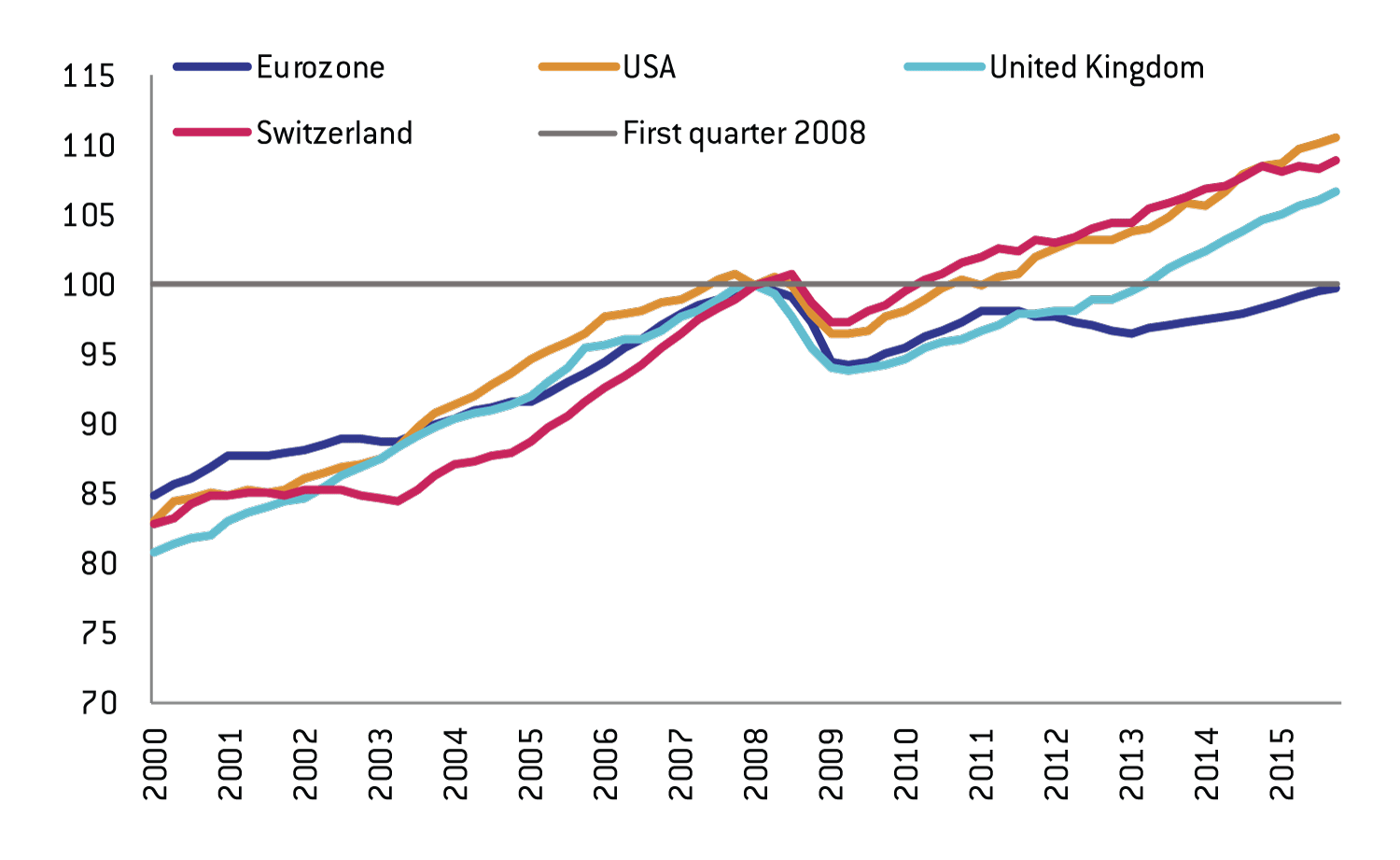

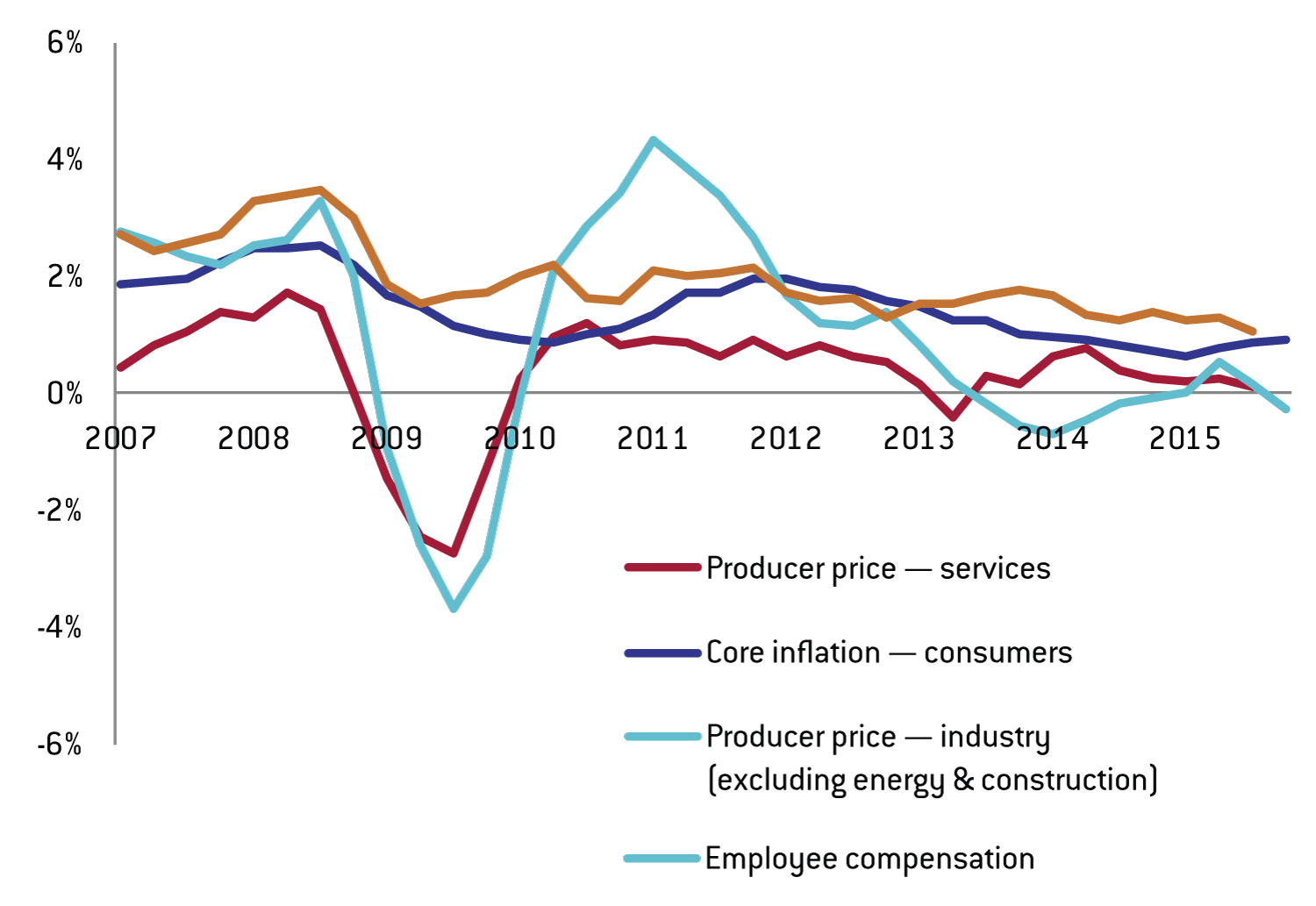

The eurozone crisis is fourfold. First, it is a growth crisis. The eurozone has only now reached the levels of economic performance that were seen before the 2008 financial crisis. In addition, the eurozone continues to suffer from high levels of unemployment and excessively low inflation, which is only partly due to the sharp fall in oil prices. Even core inflation, which excludes energy prices, has been at 1% for a long time, and producer price inflation for goods and services is even lower. Employee compensation is growing increasingly slowly, most recently by just 1% annually. Those are all classic signs of low demand.

Figure 1: GDP (Real GDP index)

Figure 2: Inflation

In addition, there are considerable weaknesses on the supply side. The eurozone is suffering from excessively low growth in productivity. In 2002–2015, value added per employee grew by just 0.5% per year on average. The reason for that is not the industrial sector, where the figure is almost 2%, but the services sector, where productivity growth is very low and in some cases even negative. The services sector lacks innovative drive and investment. Such problems of structural growth cannot be solved by demand policy alone.

Figure 3: Employment and labour productivity growth

The second crisis, the debt crisis, still has a firm grip on large parts of public sector budgets across Europe, reducing their fiscal room for manoeuvre. It is also reflected in the over-indebtedness of some businesses and private households. That calls for consolidation. However, amid a growth crisis, that is a very hesitant process, particularly given the high real costs of financing, once the very low inflation rates are taken into account. That also weakens demand. The result is a vicious circle, which inevitably exacerbates the third crisis – the banking crisis.

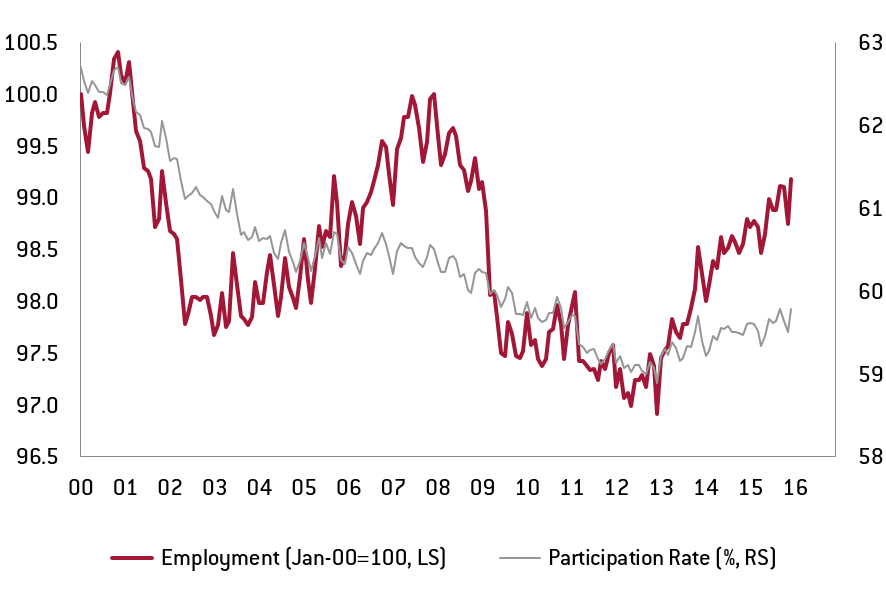

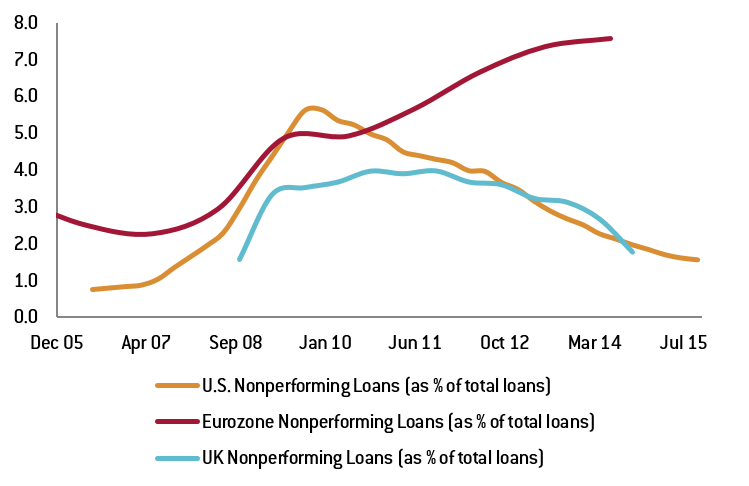

Numerous southern European banks are afflicted by bad loans of hundreds of billions of euros, reducing their willingness to grant new loans. There is an urgent need for value adjustment here, combined with a corresponding increase in capital. Additionally, banking systems, including in Germany, remain over-saturated. Low interest rates and rising regulatory costs, which are themselves the result of the financial, growth and debt crises, and the related difficulties in generating profits, all pose significant challenges to banks throughout the eurozone.

Figure 4: Nonperforming loans in the US, UK, and the eurozone

The fourth crisis is a crisis of confidence. Businesses do not invest and people do not consume if they lack confidence in the ability of policy-makers to solve Europe’s economic problems, if they are concerned about unemployment and lower wages, or if they anticipate low demand for their own products. That lack of confidence makes it all the more difficult to overcome the European crisis.

These four crises, which are closely connected and exacerbate one another, will not solve themselves. The ECB is one of the few institutions that is contributing to the solution. In doing so, it is acting in line with its mandate of ensuring medium-term price stability by means of monetary policy instruments. The reasons for that mandate are twofold. First, stable prices are a necessary condition for healthy and sustainable economic development and demand. Excessively low price development have also recently gone hand in hand with higher real interest rates. That reduces utilisation of productive capacity and tends also to lessen medium-term growth potential. Second, stable price development allows private households, parties to collective wage agreements, businesses and investors to plan ahead, which is essential when entering into long-term contracts.

The ECB, like many other central banks, defines price stability as inflation of just below 2%. Not only is the ECB clearly short of that target at present, but it also seems to be out of reach in the foreseeable future. Market-based and survey-based inflation expectations for the coming years are significantly below that mark. If the ECB failed to use all the instruments at its disposal under these circumstances, it would be in breach of its mandate and would risk damaging its credibility.

However, monetary policy is not a panacea without side effects. Monetary policy always has an impact on the distribution of income and assets. In addition, there are potential risks in terms of financial stability – lower interest margins put pressure on banks’ bottom lines, potentially tempting them to take higher risks. Low interest rates can also lead to bubbles in asset prices.

All that is true, but raises the question of what would happen if the ECB instead did nothing, which is what some German critics would evidently like to see. What would have happened if the ECB had not implemented its support programmes? The Swedish Riksbank, for example, long held out against rate cuts in the last few years, out of concern for financial stability. As a result, inflation kept on declining, and Riksbank was later forced to cut rates all the more sharply. Its rates are now below those of the ECB.

There are some indications that the low interest rates and purchase programmes of the ECB have had an effect over the last year and a half – they have lowered long-term interest rates, strengthened lending in southern Europe, even if only slightly, and allowed for the devaluation of the euro, which promotes exports (particularly in Germany). On the other hand, ECB inaction would likely have resulted in even lower inflation, even lower levels of growth, and even higher unemployment. Early and decisive action is crucial for the success of monetary policy.

We believe that the ECB’s measures are correct and necessary, but not sufficient to pull the European economy out of the crisis – all players, including the ECB, have responded too hesitantly for that to happen. In addition to proactive monetary policy, decisive action by politics is needed with respect to three other areas of the fourfold problem.

The first area that should support monetary policy is fiscal policy. It is largely cyclically neutral in Europe now – after years of anti-cyclical cuts, which were often made in the wrong places (investments). Europe urgently needs a threefold rethink of fiscal policy. First, investment must be strengthened and government consumption must be put on a sustainable footing. Countries like Germany, for example, invest far too little in infrastructure and education. They are saving at the expense of the future, for example by neglecting spending on maintenance. At the same time, many European countries – including Germany – must reform their social security systems, which are under pressure due to demographic changes and low potential growth. That should involve long-term measures, so as not to exacerbate the currently weak demand.

In addition, the fiscal leeway of the Fiscal Pact should be used to its full potential. The economic situation in Europe is too critical for fiscal consolidation and debt reduction to be top priorities. This is especially true of strong countries like Germany, which should not prioritise a zero deficit (termed the “black zero”) in view of the refugee crisis and many years of negative net public investment. Neither the German debt cap nor conventional economic analysis require Germany to have a zero deficit. Instead both require fiscal policy that can be more expansive during these difficult times in Germany, in order to spend on important matters and make vital investments.

And the eurozone needs a plan for sustainable fiscal policy in all countries, in order to make public debt viable in the long term. Governments will only have the necessary fiscal leeway to take countermeasures in difficult times (such as now) if a credible, sustainable fiscal policy is in place. Consolidation and debt rules can, however, be difficult to impose from the outside, as experience shows. Fiscal rules must be developed and accepted by means of broad dialogue in Europe. That dialogue must include the questions of the overall impact of the fiscal policy of all countries in the eurozone, if monetary policy reaches its limits, how socially acceptable consolidation works, and how state investment can be maintained during consolidation phases.

The second area consists of structural reforms, which must continue to be implemented in order to increase growth potential. In the current situation, it is vital for Europe to identify and quickly implement such reforms, which will help to overcome weakness in demand and also foster productivity growth. In addition to country-specific problems, which are currently pressing in Italy and France, Europe should focus upon opening markets and promoting the internal market for services. Particularly in private services, European productivity growth lags significantly behind on a worldwide level, owing to markets that are too small and are protected by non-tariff barriers. A large, European market, on the other hand, would encourage more investment, especially in modern technologies. However, a comprehensive, productivity-focused, European services agenda requires Germany, which acts as one of the main brakes on it, to lead the movement.

The third area is the banking sector. The eurozone will see considerable consolidation of the banking sector in the coming years. Perhaps the biggest difference between the USA and the Eurozone is that, after 2008, the USA rapidly cleaned up its banking sector, thereby laying the groundwork for ending the crisis and for economic recovery. Banks experiencing difficulties have often performed their role as financiers of the European real economy only in the sense of continuing to finance existing, non-sustainable economic structures, therefore contributing to maintaining extensive portfolios of problem loans.

The banking union was an important step towards a healthy European banking sector, but it is far from achieving that goal. A faster solution to non-performing loans would eliminate insecurity, offer indebted households and business a new perspective, and make bank capital available for new loans to productive businesses.

German critics of the ECB make two big mistakes. First, they overlook the fact that, for all the side-effects of current ECB monetary policy, the consequences of inaction would be much worse. Second, they offer no constructive alternative to monetary policy, and risk damaging the ECB’s credibility with their criticism. It is unlikely that the ECB will be able to fulfil its price stability mandate through its monetary policy measures alone, but structural reforms will not single-handedly solve the European crisis either. The still dysfunctional banking sector in the eurozone prevents the financing of meaningful and productive investments. Fiscal policy is still insufficiently focused on investment and growth, and it is too restrictive in countries with fiscal leeway.

Criticism in Germany of the ECB is counter-productive. Monetary policy must remain expansive so that it can at least begin to fulfil the ECB mandate. The preservation of its credibility also demands that. Instead of the ECB doing less, European policy-makers must do more. They need to act more decisively to set Europe back upon a growth path. Policy-makers, including in Germany, can no longer shirk their responsibility for the current economic situation in large parts of Europe. That calls for growth-friendly fiscal policy, structural reforms to open up new markets and consolidation and restructuring of the financial sector. We in Germany, above all, must look in the mirror, because we need the majority of these reforms just as urgently as our European neighbours do.