The ECB will have its next monetary decision meeting on Thursday. Instead of following politically motivated statements that complain about low nominal rates, the ECB needs to focus on its mandate: price stability, defined as inflation rates close to but below 2% in the medium-run. So what do data on inflation dynamics and on the risks for euro area inflation tell us?

This post was first published by Bruegel.

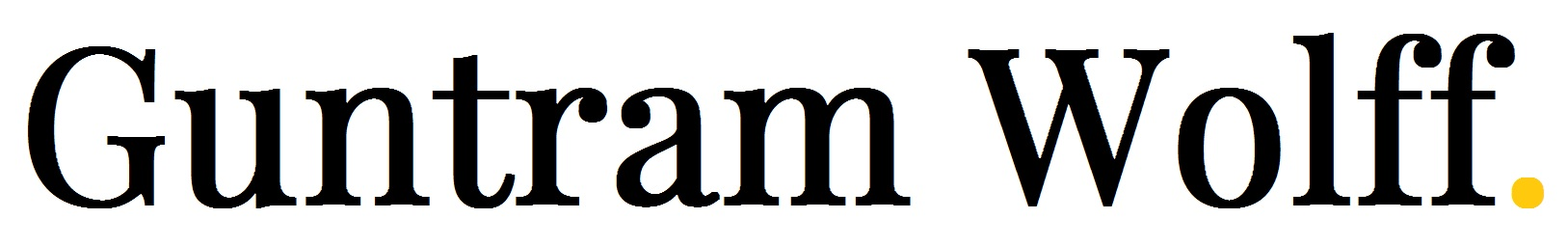

Let’s start from the observable facts. Euro area inflation has been falling since 2011Q4 and while there was a short pick-up in early 2015, it has fallen again recently. The recent fall, however, is less clearly visible in core inflation rates. Core inflation, i.e. inflation rates excluding prices for commodities that have recently fallen, has been rather stable at slightly below 1% since mid-2013. Observable inflation rates therefore speak for an easing bias rather than a tightening bias in monetary policy.

Figure 1: Headline and core inflation in the euro area

Source: Datastream

Second, the price stability mandate is, of course, not about current inflation rates but rather medium-term expected inflation rates. A number of worrying indicators appear. Market-based inflation expectations have fallen since the summer. While in July markets were still expecting inflation to be at 1% in 2017, the expectation is now only slightly above 0.5%.

Figure 2: Market-based inflation expectations

Source: Datastream

Notes: Market-based inflation expectations are based on one to ten year inflation-linked swaps.

The ECB itself got its inflation forecasts often wrong in the past. The figure shows that compared to actual inflation, the ECB’s own forecasts tended to show an increase in inflation rates. In March the ECB was still forecasting inflation to be at 1.5% in 2016 and this number has already been revised downward to 1.1%.

Figure 3: Actual inflation vs ECB forecasts

Source: Datastream, ECB Staff Macroeconomic Projections

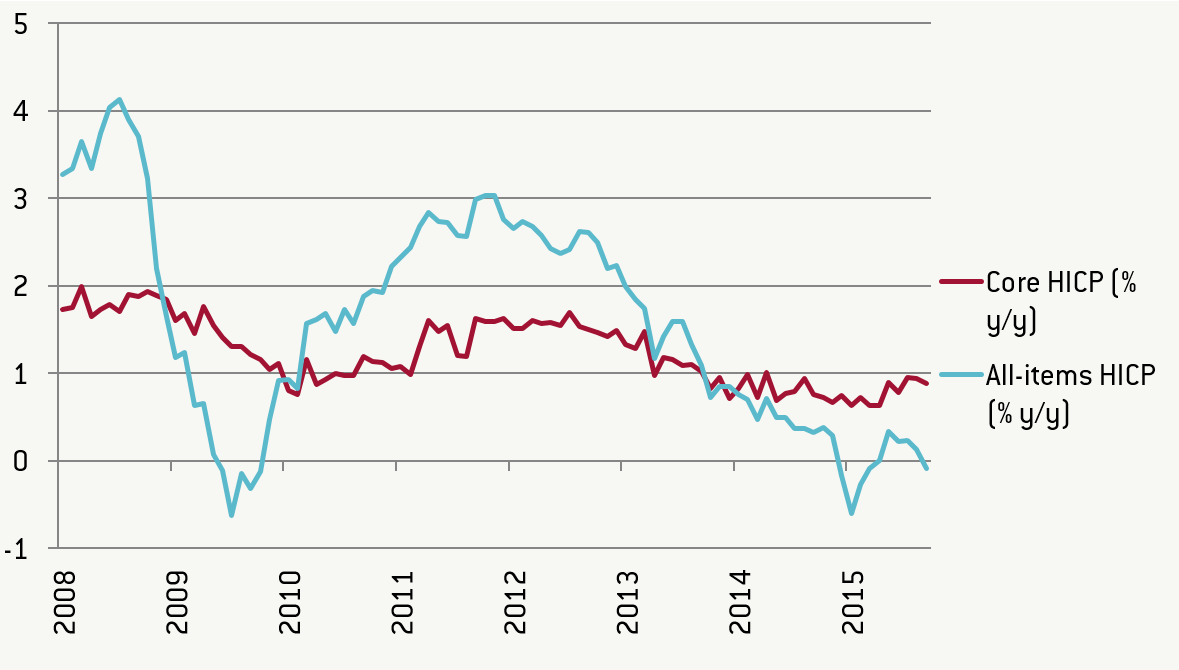

The survey of professional forecasters (SPF) does not yet show a decline in inflation expectations but it also failed previously to forecast the decline in inflation rates (see chart). Moreover, the two-year-ahead inflation forecast suggests an inflation rate of only 1.5%. Again, this number would certainly speak against a tightening of monetary policy.

Figure 4: Inflation vs what was forecast

Source: Datastream

Third, the ECB should learn from past mistakes and shift towards more active risk management. The ECB should end denying the risk of undershooting inflation expectations. True, some of the reasons for lower than expected inflation rates were exogenous factors such as a decline in commodity and oil prices. However, taking the numbers shown above together shows a clear picture of strong deflationary tendencies at work in the euro area. This is a major risk for policy making in the euro area. The lower inflation expectations are, the higher will be the real interest rate and the more difficult it will be for the ECB to prevent further deflationary tendencies. With constrained fiscal policies, the euro area may end up in a low-inflation trap from which it will not be able to escape. The consequences for debt sustainability and delayed macroeconomic adjustment have been discussed compellingly and at length. Conversely, the risk of overshooting the 2% inflation target is not only very low. It is also a risk that can far more easily be managed should it materialize by simply changing interest rates. The case for more active policy to prevent undershooting of inflation rates is therefore compelling.

Fourth, beyond the inherent domestic deflationary tendencies that risk undermining the ECB’s goal, also the global economy faces a number of important risk. Most importantly, there is uncertainty about China. The US Federal Reserve has just delayed a rate increase, and one of the main reasons for this delay was fears about the US economy because of the economic situation in China (as was clearly pronounced by New York Federal Reserve President William C Dudley at an event at Brookings). One can debate endlessly whether or not the Chinese political system will manage to engineer a soft landing of China’s economy. But unless we are a 100% certain that China will economic policy should manage that risk. We have shown before that a sneeze of China has implications for Europe’s stock markets through simple trade channel effects. The ECB should therefore follow the lead of the Fed and carefully consider the risk China poses to fulfilling its price stability mandate.

The ECB, as an independent monetary authority, should be conscious of the risks that failing to fulfil its mandate pose. It should accept that inflation expectations have deteriorated and core inflation remains stubbornly below 1% while the global economy faces a number of risks that could have effects on the euro area.

At the very least, the ECB should continue its ongoing QE programme and clearly dispel doubts that it could bow to political pressures and end its programme prematurely. The ECB was right to expand its list of assets eligible for purchases further after its decision to start sovereign QE in January. A longer list would allow increasing or lengthening the purchase programme. In fact, the ECB could even consider dropping the 25% purchase limit on sovereign bonds with AAA rating. The purchase limit is a sensible measure on bonds with CACs to prevent the ECB from having a blocking vote in debt restructuring decisions. But it would be wrong to constrain QE because of this for bonds with very low risks. An announcement by the ECB to use this option and extend purchases into 2017 would be a strong message that the governing council is serious about risk management. Adding a small-scale programme to support the corporate bond market would be another option to consider. Governments, in turn, should focus on their task of reforming euro area economies so that new investment opportunities arise.