Strengthening the banking system is important to achieve a sustainable recovery, because it will revitalise credit to the healthier segments of the economy. However without restructuring, euro area banks are still vulnerable.

This opinion piece was first published by Expansion, Il Sole 24 Ore, Kathemerini, Handelsblatt, and Diario Economico.

The euro area’s biggest banks have reported record profits. The stress tests published by the European Central Bank late last year showed that the largest banks—those with assets of more than €500 billion—have been able to cut their non-performing exposures and increase their provisions. But the euro area banking system is not out of the woods. The vulnerabilities lie in the small and medium-sized banks, those with assets below €500 billion. Together these banks own 50% of the euro area banking system assets.

In our research, based on 130 euro area banks directly supervised by the ECB, we find that banks are often superficially well capitalized—their regulatory capital ratios and even their equity capital looks reasonable. Only one in ten small banks has equity less than 3% of its assets; one in six medium-sized banks has an equity/asset ratio below 3%. But banks are vulnerable either because they have a high share of non-performing loans or they have insufficient resources to cover for possible losses on the non-performing loans. This is a widespread problem but one that is especially acute in the countries that have faced high stress since the start of the crisis.

To identify the troubled banks, we asked a crude but simple question. If 65% of non-performing loans have to be written down, how many banks would still have equity that is at least 3% of the bank’s assets? The answer, we find, is that about a third of small banks, with almost 40% of small-bank assets, would fall below the 3% equity threshold. Medium-sized banks would face similarly extensive stress. By comparison, only one of the euro-area’s 13 “large” banks would be considered stressed under our enhanced stress test.

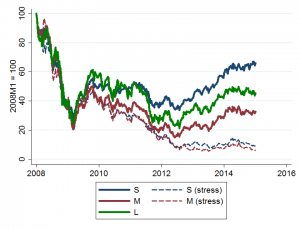

Corroboration for our findings comes from bank share prices. While the stock prices of all banks are still well below their pre-crisis peaks, the small and medium-sized banks that we identify to be stressed have had particularly weak performance. Even this understates the problem since many of the most stressed banks are unlisted. If our scenario were to unfold, the stressed assets of the small and medium banks would add up to about €3.6 trillion, about 38% of small and medium bank assets—and 16% of entire euro-area banking system assets.

Evolution of banks’ stock market prices

Source: Bruegel using data from Thomson Reuters Datastream. Note: Number of listed banks: 45 (23 Small, 12 Medium, 10 Large).

The troubled banks tend to serve a narrow range of geographically concentrated customers. As the local economy suffers, so do the banks, which, in turn, further hurts local economic prospects. This vicious cycle keeps non-performing loans high—and growing. But despite such localization, their stock price movements were highly synchronized in the early phase of the crisis, as if there were contributing to the broader systemic tensions. In other words, at moments of panic, they add to the panic well beyond the communities they serve.

For dealing with banking vulnerabilities, European policymakers seem wedded to a single response: to pump more capital into the banks. Even after the ECB’s latest asset quality review and stress tests, the entire focus was on how much more capital the banking system needed. Indeed, critics focused mainly on whether the official estimates for recapitalization were too low.

We also believe in well-capitalized banks—with the focus on equity rather than on fuzzy regulatory capital. But the real problem in Europe is that the banks in trouble have had long-standing governance problems. Often they are either government-owned or have links to the government. They have long been the source of patronage and unhealthy lending practices. Even if the new supervisory system helps clean up some of these past pathologies, the question still must be asked: what economic purpose do these banks serve? The continuing problems in Europe’s smaller banks are sending a message: Europe has a problem of overbanking.

The bottom line is that the euro-area’s banking sector needs pruning. In the United States, hundreds of banks have been closed or merged since the start of the crisis—the bulk of such action was taken quickly so that the problems would not fester. In the euro area, after much effort, the authority to resolve banks has now been standardized across the member states. Yet, there has been little action. Despite rules to impose losses on banks’ owners and creditors, there remains a reluctance to do so.

It is well past time to aggressively restructure, consolidate and close the weakest euro area banks. Failure to do so will act as a drag on economic recovery, much as it did in Japan.